In all the years that I’ve been writing and thinking about kids and parenting, the best piece of advice I got was from my dear, late father in-law, Dennis. We had just brought Anna home from the hospital, and I was panicked. How in the world was I going to raise this tiny, vulnerable girl to womanhood? “Just love her,” Dennis said. “The rest will fall into place.”

Anna is almost a legal adult. Adam is not too far behind. For these past 18 years, I’ve just loved them.

Parents in various cultures bring up their children in distinctive ways. My Connecticut grandma and Cuban abuela had very different ideas about caring for an infant. Grandma thought that I shouldn’t be held too much and that I should “cry it out” until I fell asleep from exhaustion. Abuela wanted to hold me day and night, feed me on demand and let me nap in her arms. But for all the different ways we care for our children, many of us can relate to some of the values of “attachment parenting.”

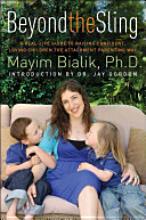

Mayim Bialik, the actress and scientist, is a passionate advocate of attachment parenting in her new book, Beyond the Sling. You may remember Bialik from the movie “Beaches,” in which she played the Bette Middler character as a child. Bialik went on to star in her own television show, “Blossom,” in the ’90s and now appears in the sitcom, “The Big Bang Theory.”

Mayim Bialik, the actress and scientist, is a passionate advocate of attachment parenting in her new book, Beyond the Sling. You may remember Bialik from the movie “Beaches,” in which she played the Bette Middler character as a child. Bialik went on to star in her own television show, “Blossom,” in the ’90s and now appears in the sitcom, “The Big Bang Theory.”

Bialik – who studied Hebrew and Judaism and pursued a doctorate in neuroscience – cites eight basics for attachment parenting:

• Natural childbirth

• Exclusively feeding a baby breast milk

• Taking the time to formulate sensitive and thoughtful responses to your children

• Bonding through touch

• Co-sleeping

• Consistent parenting by a primary caregiver

• Gentle positive discipline, which means no corporal punishment

• Balancing your needs with those of your child

Bialik comes across as a supportive, informative friend, but that doesn’t dilute her fervency. For example, she’s an unequivocal proponent of natural childbirth. However, a drug-free delivery or a home birth is not an option for everyone. Sometimes there are complications like preeclampsia or gestational diabetes, both of which I had. My water also broke six weeks before Adam’s due date. Bialik considers extenuating circumstances, acknowledging that what worked for her and her family may not be safest or right for another family.

Much has been written about the salutary effects of breastfeeding for mother and child. Bialik anticipates the health and psychological challenges of nursing a baby. She acknowledges that there can be obstacles, but her message is to keep trying to do the best you can. I think she’s on target with that advice.

Sensitive and thoughtful responses to your children may seem obvious in parenting. Getting into that mindset connects with gentle and positive parenting. No hitting. No excuses. The one exception in my experience was the time a 2- year old Anna ran into the street, and I patted her bottom with some force. (I did not spank her). She was surprised, but not in any pain. What did hurt were her feelings. Afterward, she remembered not to approach the street without an adult.

But raise your hand if encouraging your children has sometimes crossed into pressuring them. I’ll raise two hands. And I’ll give you a textbook example of a mistake that I recently made. Adam came home last week with a nice report card. But I couldn’t leave well-enough alone. I suggested that maybe next term he could turn a couple of those B pluses into A’s. At first glance, it seems as if I took Adam’s hard work for granted. What I really did was to take my son for granted, and that was just plain wrong. Bonding through touch has always been a big issue for me. In my mind it links up to co-sleeping, which Ken wasn’t thrilled about when our children were babies. Our kids squirmed and kicked a lot. Nevertheless, I undid all of his scheduling and behavior modification around sleep when he was on business trips.

There are also controversial assertions in Beyond the Sling. For example, Bialik and her husband chose not to have their children vaccinated – a subject that has been addressed by others with much greater knowledge than I. She notes that her two young sons have never been on an antibiotic. Instead she pays careful attention to her sons’ body cues and manages their health accordingly. While her children’s well-being is a blessing, we all know that at times children need serious medical intervention. Bialik, the neuroscientist, points out that thousands of years of evolution have hardwired us to protect and raise our children. She emphasizes that a parent’s intuition is the first and best line of defense in childrearing. She also captures the bittersweet arc of a child gradually moving from dependence to independence.

Time with small children is fleeting. Just love them. That’s the charming, enduring subtext of Beyond the Sling.