I am a feminist Jew because I am the mother of a daughter and a son.

I am a feminist Jew because the God of my foremothers doesn’t recognize a caste system. When my G0d blessed Jacob’s children, he also blessed Jacob’s concubines, Bilhah and Zilpah. Yet it astounds that mentioning the God of my foremothers – the imahot – is still optional in the Conservative Jewish liturgy. To my mind, this sends a message that the imahot can be optional in the hearts and souls of our children.

I am a feminist Jew because I’m angry over the injustices too frequently lorded over Jewish women.

A few years ago, my children’s day school finally included the imahot in every prayer service. But it came after a struggle. The message that landed in my mailbox announced that in consultation with local Conservative rabbis, the school decided to include the imahot in the Amidah as standard practice. Amen. And yet the message felt perfunctory to me, as if our foremothers were shadowy figures. Had Abraham, Isaac and Jacob finally decided to share their God?

Perhaps lost in redaction, our foremothers are not mentioned as a group in the Bible, but thank goodness they star in many ancient and modern midrashim as role models and prophets.

I am a feminist Jew because Sarah was said to be a greater prophet than Abraham. She understood that God didn’t demand the sacrifice of her first-born son. During her pregnancy, Rebekah knew that she had two great nations inside of her, but that the fate of the Jewish people rested with her younger son. These women triumphed over infertility and infidelity (even when they sanctioned it). I am a feminist Jew because the imahot are summoned to help the Jewish people in times of distress. Rachel was buried at a strategic place on the road where she can hear the cries of her people in captivity. Her prayers uniquely move God on their behalf.

I am a feminist Jew because prayer is instinctively beautiful for Jewish women.

Prior to the modern debate over whether to include the imahot in the liturgy, women had the wisdom and clarity to call upon them in their own prayers throughout the centuries. The imahot are front and center in the techinot, prayers of Jewish women from medieval times through the 19th century.

I am a feminist Jew because our foremothers were called upon to help Jewish women express their deepest desires and most fervent hopes in both set and spontaneous prayer.

I am a feminist Jew because I can frequently call upon the God of my foremothers. God of Sarah, hear my prayers to keep my children safe in planes, trains, automobiles and all manner of place and time. God of Rebekah, help me to recognize perilous situations. God of Rachel, help me guide my children through disappointment and desperation. God of Leah, comfort me when someone doesn’t love my children the way they deserve to be cherished.

I am a feminist Jew because the G0d of Bilhah and Zilpah brings women to the foreground where they belong.

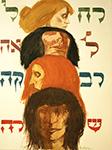

Some sources – the sources that shaped my vision as a feminist Jew – acknowledge Jacob’s concubines, Bilhah and Zilpah – the mothers of four of Israel’s 12 tribes – as matriarchs, bringing the number of imahot to six. In terms of Jewish symbolism, six corresponds to the six days of creation. Who on earth has been more responsible for the creation of the Jewish people than Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, Leah, Bilhah and Zilpah?

I’ve read about the brouhaha of nursing a child in a public space. I am a feminist Jew because I know that Sarah, a mother who weaned her own child when he was 3 years old, would have defended these women asserting their right to be mothers. Rachel would have heard the cries of those hungry babies and interceded so that their mothers could do the most natural and loving thing in the world for their children – nourish them.

Leah continues to hear the prayers of all mothers who send their children to serve their countries in dangerous places. Rebekah hovers near mothers who must make tough choices for their children. Bilhah and Zilpah understand women who feel marginalized.

I am a feminist Jew because women recovered Leah’s story to teach my children and their children that the woman thought to be plain with weak eyes, was as strong and holy as her husband.

One of my favorite midrashim on the imahot addresses the order in which the matriarchs appear in the liturgy – God of Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah. After the name Leah appears in the text, the next word is Ha-el – The God. Ha-el is Leah spelled backwards. This wordplay elevates Leah from second class wife to matriarch. Hers is the last name to linger after the initial blessing. Hers is the name that inverts the name of God.